By Joana Trinidade and Inês Santos

Following the presentation delivered last spring in Montemor-o-Novo (Portugal) by DASH team member Ivana Momić (Serbian Association of Urban Planners), we were hosted in Serbia by the Public Enterprise for Urbanism and Construction of Leskovac (UCL) where Ivana is working urban planner. After an initial theoretical brief on the methodology of citizen engagement in land-use planning, developed by Zlata Vuksanović-Macura from GIJCSANU, the visit provided the opportunity for Minga DASH members to see from up close the area where one of the projects that implemented this methodology took place.

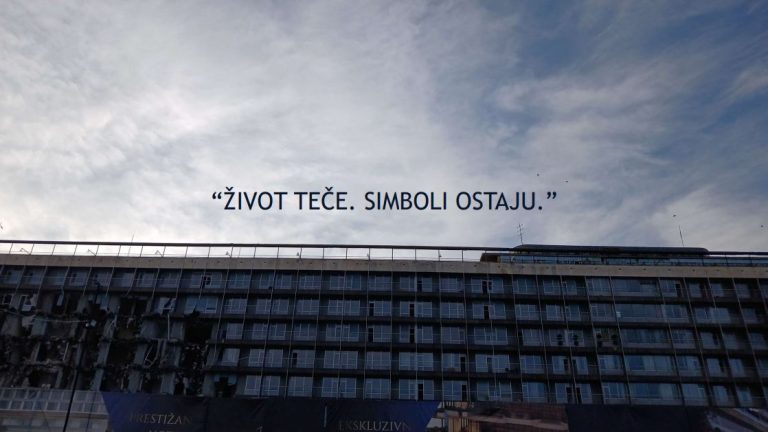

Credits for images: Inês Santos

The participatory methodology framed by Zlata Vuksanović-Macura was introduced in Leskovac through a governmental program implemented in 11 municipalities around Serbia between 2018 to 2020. The program sought to test a novel model for participatory urban planning, recognizing the lack of success of the current mandatory legal tools in facilitating community engagement in urban planning. With the goal of engaging and empowering marginalized communities, a diverse set of Roma neighbourhoods was included in the program throughout the country, Slavko Zlatanov being one of them.

The program was designed in different phases that could run in parallel to the normal planning procedures, so that the two processes could influence each other directly and dynamically. These phases were: initial consultations with inhabitants; consultation surveys; establishment of the Settlement Committee; in-situ education of inhabitants; and building consensus. The model proposed moving one step ahead of the mandatory urban planning procedures of “Early public review” and “Draft for public review”. In Slavko Zlatanov, the participatory intervention’s main goal was to develop a detailed plan, identifying planning expansion areas, connections to public infrastructure, and so forth – and, importantly, to provide the opportunity to regularize undocumented self-built homes.

On our arrival at Leskovac, we met UCL’s large team of urban and architectural planners, assistants, lawyers, as well as UCL’s director. We had the opportunity to talk with some members of the team and met the coordinator of the participatory program’s implementation in Slavko Zlatanov, as well as UCL’s community mediator, who accompanied us on all of the visits to the neighbourhood. Ivana guided us through Slavko Zlatanov, a self-built Roma neighbourhood with around 2000 inhabitants (5.34% of the 144,632 inhabitants in the municipality), which is experiencing significant challenges in intergrating into the fabric of the formal city.

Our first stop was the neighbourhood’s cultural centre, a gathering place for the local residents. The centre is located in the old part of the neighbourhood, streets are smaller and sinuous, and townhouses are the most common typology. As we move away from the centre, streets become larger, and houses become bigger and detached. A denser urban life, with a lot of people in the streets, especially kids, is felt in the centre when compared to the newer parts. Houses in Slavko Zlatanov are built in different styles and sizes, most of them 2-3 stories high, so that they can accommodate different generations of the same family. As far as we could observe, houses are built in an incremental way throughout the years: in the first phase the first floor of the house (including a roof) is built; in the second phase windows are installed and the ground floor is finished; the additional stories are often added later on, depending on the financial capacity of each family – which usually depends on money being sent by family members working abroad (and mostly in Germany).

The residents’ committee then joined us to visit the church, which was the first protestant church in Serbia, and aimed to gather together all communities, independently of their ethnicities. We all had the chance to sit round a table with the pastor and other members of the church, trying to glean more detailed insights into the historical, social, religious and economic aspects of the neighborhood.

In a cooperative, the environment that needs to be established for active decision-making is very similar to that needed for effective participation that leads to personal, social and economic empowerment. Principles include transparency; power and responsibility sharing; recognition of individual voices within the collective; and no discrimination on the basis of culture, origin, gender, religion etc. When it comes to land-use planning, how can the city integrate different needs and desires while aiming at a common goal of access to appropriate housing within legal frameworks?